|

| |

Back

to Articles Menu

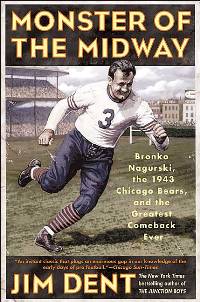

Book Report: Monster of the Midway

by

Randy Snow

Originally

posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Wednesday, June 8, 2011

One of

the most recognizable names in pro football history has to be that of the

legendary Chicago Bears player, Bronko Nagurski. In the 2003 book, Monster of

the Midway, author Jim Dent tells the story of Nagurski's life and football

career, from a simple farm boy in Minnesota to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

He

is regarded as one of the toughest players ever in the NFL, a powerful running

back and blocker as well as a top defensive lineman who could stop opposing

runners cold. Is it any wonder that the Chicago Bears earned the nickname, "The

Monsters of the Midway", during the Bronko Nagurski era? He

is regarded as one of the toughest players ever in the NFL, a powerful running

back and blocker as well as a top defensive lineman who could stop opposing

runners cold. Is it any wonder that the Chicago Bears earned the nickname, "The

Monsters of the Midway", during the Bronko Nagurski era?

Bronko's father, Nicholas Nagurski, emigrated from Poland to Canada at the age

of 19. In those days, immigrants from Europe who wanted to come to America, but

did not have any relatives in the U.S., had to go to Canada first. Nicholas only

had a third grade education, but was a hard worker and was very intent on

eventually making it to America.

In 1907, Nicholas married Michelina Nagurski, his fourth cousin, who had

traveled from Europe on her own to be with him. Bronko was born in 1908 in Rainy

River, Ontario. He was the first of the couple's four children. His real name

was Bronislau, but his first grade teacher nicknamed him Bronko because the

other children in his class were having a hard time pronouncing his name.

The family came to America in 1912 and settled in International Fall, Minnesota.

Nicholas started out owning a local grocery store but though hard work he also

owned a construction business as well as a sawmill and a real estate company.

Bronko was a star player on the high school football team in his junior year,

but the rest of the team was terrible. They lost every game that season. The

summer before his senior year, the coach in Bemidji, Minnesota, about 30 miles

south of International Falls, sent a message asking if Bronko wanted to transfer

and play for him. Since Bemidji had a much better team, he decided to leave

International Falls. Bemidji was also a place where college recruiters came

looking for prospects and Bronko really wanted to play college football.

The superintendent at International Falls lodged a complaint with the Minnesota

High School Athletic Association over the transfer and Bronko was suspended from

playing sports in his senior year. He was allowed to practice with the Bemidji

team, however, and received offers from a few small colleges, but none were to

his liking so he turned them all down.

In the summer of 1926, after Bronko had graduated from high school, he was back

home in International Falls. One day he was plowing a field when a man in a

green Ford stopped by. It was Dr. Clarence "Fats" Spears, the coach of the

University of Minnesota. The two spent the afternoon fishing together and Bronko

agreed to play football for Minnesota.

Nagurski had a great college career playing for the Gophers. However, his

parents and sibling only made it to one of his games. It was the last home game

of his senior season in 1929. After the season, famed sportswriter Grantland

Rice named Nagurski to not one, but two positions on the annual All-American

Team. He was selected at fullback as well as defensive tackle. Rice had taken

over compiling the list following the death of Walter Camp in 1924.

Nagurski went on to play in the post-season East-West Shrine game in San

Francisco. After the game, Chicago Bears coach and owner George Halas approached

Nagurski on the field. In his hand was a contract for Bronko to play for the

Bears in 1930 for the sum of $5,000. He signed the contract on the spot.

Training camp for the Bears in 1930 was held on the campus of Notre Dame

University in South Bend, Indiana. That year, George Halas stopped playing on

the team and also chose Ralph Jones to take over as Bears head coach so that he

could spend more time concentrating on running the team and building the NFL

into a more stable and profitable league.

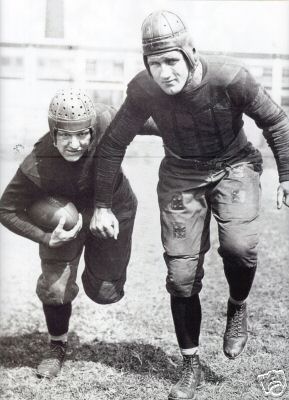

Another player on the Bears team that year was the legendary Red Grange, who had

re-signed to play for Chicago in 1929. Grange originally signed with the Bears

in 1925, the day after his final college football game. He was the biggest name

in the NFL at the time and brought instant attention to the struggling league.

As soon as he was signed, the Bears and their new star went on a 19-game

barnstorming tour across the country. But after the 1925 season, Grange's agent,

C.C. Pyle wanted a one-third ownership for himself and Grange in the Bears.

Halas and his team co-owner, Dutch Sternaman, refused. Pyle then tried to get

the NFL to grant him a team in New York City, but the league turned him down as

well because it already had the New York Giants. Pyle decided to form his own

professional football league in 1926 as a rival to the NFL. It was called the

American Professional Football League and Grange was the star player for the New

York Yankees. Another player on the Bears team that year was the legendary Red Grange, who had

re-signed to play for Chicago in 1929. Grange originally signed with the Bears

in 1925, the day after his final college football game. He was the biggest name

in the NFL at the time and brought instant attention to the struggling league.

As soon as he was signed, the Bears and their new star went on a 19-game

barnstorming tour across the country. But after the 1925 season, Grange's agent,

C.C. Pyle wanted a one-third ownership for himself and Grange in the Bears.

Halas and his team co-owner, Dutch Sternaman, refused. Pyle then tried to get

the NFL to grant him a team in New York City, but the league turned him down as

well because it already had the New York Giants. Pyle decided to form his own

professional football league in 1926 as a rival to the NFL. It was called the

American Professional Football League and Grange was the star player for the New

York Yankees.

The APFL only lasted one year, but Pyle, Grange and the Yankees were allowed to

join the NFL in 1927. The Yankee team folded after the 1927 season. Grange had

suffered a severe knee injury that year and did not even play at all in 1928.

Grange and Pyle parted ways after the 1927 season.

As a testament to his toughness, Nagurski reportedly ran into a policeman on

horseback in a 1931 game against the Chicago Cardinals. The horse was lifted off

the ground by the hit inflicted by the Bears running back as he was forced out

of bounds on a sweep. He immediately apologized to the horse. Nagurski also is

said to have hit the brick wall at Wriggly Field so hard once after running

through the end zone for a touchdown that he put a crack in the wall.

In 1932, the Chicago Bears and the Portsmouth Spartans ended the season tied for

first place. Up until that year, the NFL champion was crowned simply by virtue

of the team with the best record. There were no playoffs or championship game

back then. But the NFL decided to add some excitement that year by holding its

first ever championship game in Chicago at Wrigley Field. However, three

blizzards hit the city over the course of 10 days and the city was buried in

snow. Instead of cancelling the game, it was decided that the game would be

played indoors at the Chicago Stadium, the place where the Chicago Blackhawks

played hockey at the time.

The Bears had played an exhibition game at Chicago Stadium in 1930 against their

cross-town rivals, the Chicago Cardinals. Just days before the 1932 NFL title

game was played, the Barnum and Bailey Circus had been at Chicago Stadium. There

was six inched of dirt already covering the concrete floor, complete with circus

animal droppings!

Chicago Stadium was not big enough to allow for a full sized football field.

Instead, the playing field was only 80-yards long; 60 for the playing field with

10-yard end zones at each end, and it was only 40-yards wide. (This is somewhat

similar to what an Arena Football field is like today.) There was only one set

of goal posts at one end of the field. Several special rules had to be adopted

for the game. There were no field goals allowed and kickoffs were from the

10-yard line. Anytime that a team crossed , mid-field they were automatically

set back 20-yards to make the stats come out closer to those played on a full

sized field.

Portsmouth was without their star quarterback/tailback, Dutch Clark, who had

already left the team for his off season job as the basketball coach at the

Colorado School of Mines.

The game was scoreless through the first three quarters. Chicago finally got on

the scoreboard in the fourth quarter when, on a fourth down play, Nagurski

attempted to run the ball over from the 2-yard line. The Spartans anticipated

the play and were ready for him. When he realized that there was nowhere to run,

he stopped short of the line of scrimmage and improvised. He took a couple of

steps back and scanned the end zone. He jumped up and threw a pass to Red Grange

that was caught for a touchdown. Portsmouth coach Potsy Clark ran onto the field

screaming at the officials. In those days, NFL rules stipulated that a legal

forward pass had to be thrown from at least five yards behind the line of

scrimmage. The officials gathered together to talk about the play, but decided

to let the play stand.

Later in the quarter, Portsmouth was punting from its own end zone. Spartan

punter Mule Wilson dropped the ball and it rolled out of the end zone for a

safety. The final score was Chicago 9, Portsmouth 0. An estimated crowd of

12,000 fans was in attendance for the game. The next day, the Portsmouth Times

newspaper ran the headline, "Sham Battle on Tom Thumb Gridiron."

During the off season, a number of significant

rule changes were implemented to make the game more exciting to watch. One of

them was known as the "Bronko Rule," which allowed for a forward pass to be

thrown from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage. They also added hash marks to

the field, which college football already had. The owners did away with the

five-yard penalty for an incomplete pass and eliminated a change of possession

rule for an incomplete pass in the end zone. Goal posts were moved from the goal

line to the back of the end zone and the ball itself was made smaller, more

aerodynamic, and easier to throw to encourage more passing. The league was also

divided into two divisions, East and West, allowing for a championship game

between the division winners to be played every year from then on.

One rule change, however, was not a popular one with most of the owners, but the

proposal passed anyway. At the urging of Boston Redskins owner George Preston

Marshall, the NFL agreed to ban black players from playing in the NFL. Blacks

had been playing in the league since it was founded in 1920.

In the summer of 1934, the sports editor of the Chicago Tribune newspaper, Arch

Ward, came up with the idea for an exhibition game between the defending NFL

champion and a team of College All-Stars. The game was played in Chicago, of

course. The Bears and Nagurski played the All-Stars to a 0-0 tie in the

inaugural game in front of 79,432 people at Soldier Field. The year before, in

1933, Ward had also come up with the idea for an All-Star game in Major League

Baseball between the American League and the National League. That game was also

played in Chicago.

Nagurski and the Bears played in the first Thanksgiving Day game in Detroit in

1934, beating the Lions 19-16. Thanks to the blocking of Nagurski that year, his

team mate, Beatty Feathers, became the first player in the NFL to rush for over

1,000 yards in a single season. Red Grange also retired after the 1934 season.

Following the 1934 season, Bronko began making extra money by starring on the

pro wrestling circuit.

During the 1935 season, Nagurski missed five games due to an ailing hip. He was

diagnosed with a Streptococcus infection in his hip and sciatica. Coach Halas

blamed it on the wrestling.

Nagurski married Eileen Kane on December 23, 1936. Their first son, Bronko

Nagurski, Jr., was born on December 25, 1937.

On June 29, 1937, after toiling in the minor circuit of professional wrestling,

Nagurski won his first world championship title. He defeated Dean Detton at the

Minneapolis Field House. On June 29, 1937, after toiling in the minor circuit of professional wrestling,

Nagurski won his first world championship title. He defeated Dean Detton at the

Minneapolis Field House.

Because of his wrestling schedule, Nagurski missed the entire 1937 preseason and

all practices. He did join the Bears in time for the first regular season game.

However, he continued to wrestle between football games through mid October. In

one 12-day stretch, Nagurski played in four football games and wrestled in nine

matches, each one in a different city!

The Bears lost to the Washington Redskins 28-21 in the 1937 NFL championship

game and Nagurski decided to retire from playing football. Constant hip and knee

problems were making it hard for him to continue on the gridiron. He did,

however, continue wrestling through the late 1950īs.

The Bears struggled on the field without Nagurski for the next few years until

the 1940 season. That's when new coach Heartley "Hunk" Anderson, took over the

team. Anderson went to high school with George Gipp in Calumet, Michigan and

also played alongside Gipp at Notre Dame. He went on to be an assistant football

coach under Knute Rockne during the days of The Four Horsemen. Anderson had also

played for the Bears during Red Grange's first season in the NFL. When Rockne

was killed in a plane crash in 1931, Anderson became the Notre Dame head coach.

Bears second year quarterback, Sid Luckman, took command of the team and its

complex T-Formation offense in 1940 and Chicago advanced to the NFL title game

once more to face the Washington Redskins. The Bears demolished the Redskins

73-0 in the most lopsided game ever in NFL history.

By 1943, the United States was fully engaged in World War II. Many NFL players

were called to active duty and were serving overseas. Even George Halas, at the

age of 47, volunteered to serve in the war. He joined the Navy and served in the

South Pacific. The shortage of players was so severe that the Pittsburgh

Steelers and the Philadelphia Eagles combined that year to field a team called

the Steagles.

Hunk Anderson convinced Bronko Nagurski to come out of retirement and play one

more season in Chicago. Nagurski was now 35 years old and had not played

football in almost six years, but he agreed to join the team. There were only

five players left on the team from the 1937 Bears squad that Nagurski had

previously played on.

Instead of playing running back, Nagurski played offensive and defensive tackle.

He opened holes for the running backs when he was on offense and he stopped

runners cold when he was on defense. Because of the lack of players in 1943, the

NFL relaxed the rule on substitutions. Previously, if a player came off the

field, he could not come back until the next quarter. That's why players played

both ways and on special teams. In 1943, the NFL allowed substitutions at any

time during the game, which was a great help to the aging Nagurski.

Nagurski showed that he could still play football at a high level even though he

only played on the line. Towards the end of the season, however, the team was

hurting for players once again as injuries and a flu outbreak on the team made

Nagurski realize that he was needed at running back once again. In the final

game of the regular season he played on the line through the first three

quarters, but in the fourth quarter, with the Bears trailing 24-14, Nagurski

took the field as a running back. He carried the ball 16 times for 84 yards and

helped the team to a 35-24 come from behind win, which put them in the NFL title

games once again.

The Bears faced the Washington Redskins yet again on December 26, 1943. It would

be Nagurski's final NFL game. George Halas was home on leave from the Navy and

was in attendance at Wriggly Field for the game in his naval uniform. Chicago

won the game 41-21. It was Nagurski's third NFL title after winning back-to-back

championships in 1932 and 1933.

Nagurski never played in the NFL again, but he did play in one final football

game. On May 17, 1958, at the age of 50, he suited up for an Alumni football

game at the University of Minnesota. He ran the ball several times during the

first quarter and even scored a touchdown which delighted the fans who had come

out to see the game. Of course, his team won 26-2.

When the Pro Football Hall of Fame opened in Canton, Ohio in 1963, Bronko

Nagurski was among those in the very first class. Two other Bears greats, Red

Grange and George Halas, were also included in that inaugural class.

Nagurski's last public appearance came in January of 1983 when he participated

in the coin toss at Super Bowl XVIII in Tampa.

Bronko Nagurski died on January 7, 1990 at the age of 81. He is buried in

International Falls, MN, the town where he grew up and lived his entire life

when he was not wrestling or playing football.

Since 1993, the Bronko Nagurski Award has been presented to the most valuable

defensive player in college football. It is presented by the Charlotte Touchdown

Club and the Football Writers Association of America.

Nagurski's son, Bronko Nagurski, Jr., played in the Canadian Football League for

eight seasons. He played college football at Notre Dame and was drafted by the

NFL San Francisco 49ers in 1959, but opted to play in Canada instead. He played

offensive tackle for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats from 1959-1966, winning two Grey

Cup championships in 1963 and 1965. He died on March 7, 2011 at the age of 73.

ROAD TRIP

If you are ever in International Falls, make sure you visit the Bronko Nagurski

Museum. It is located at 101 Sixth Avenue.

Back

to Articles Menu

|