|

| |

Back

to Articles Menu

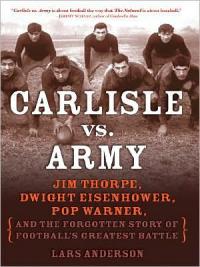

Book Report: Carlisle vs. Army

by

Randy Snow

Originally

posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Sunday, June 22, 20087

In the new book, Carlisle vs. Army,

author Lars Anderson explores the lives of two very different people, legendary

athlete Jim Thorpe and future President of the United States, Dwight D.

Eisenhower.

On the surface, it is hard to imagine what these two men could possibly have had

in common, but their lives crossed paths one afternoon in 1912 when they met

face-to-face during a college football game.

Eisenhower

grew up in Abilene, Kansas and graduated from Abilene High School in 1909, along

with his brother, Edgar. Ironically, their high school yearbook predicted that

Edgar would someday become the President of the United States while Dwight would

become a history professor at Yale. Eisenhower

grew up in Abilene, Kansas and graduated from Abilene High School in 1909, along

with his brother, Edgar. Ironically, their high school yearbook predicted that

Edgar would someday become the President of the United States while Dwight would

become a history professor at Yale.

Dwight Eisenhower loved to play baseball and football when he was growing up.

The summer after he graduated from high school, he played baseball in the

Central Kansas League. He knew that if word got out that he had received money

while playing baseball that summer, it would keep him from playing football in

college, so he played under the name, "Wilson." That same summer, in North

Carolina, Jim Thorpe also played baseball for money. However, Thorpe used his

real name, something that would cause him to lose his two Olympic gold medals a

few years later.

Both Edgar and Dwight Eisenhower , wanted to go to college after high school,

but neither could afford it on their own, so they came up with a plan. Dwight

would work a job and pay for Edgar to go to the University of Michigan for one

year. Then Edgar would work the following year and pay Dwight´s way through

college. If they stuck with the plan, both of them would have their college

degrees in eight years. But after working for just one year, Dwight applied to,

and was accepted at, West Point.

Eisenhower wanted to play on the varsity football team his first year at the

Army Academy, but was assigned to the junior varsity team instead. Over the next

year, he worked hard at improving his speed and putting on some weight to

impress the varsity coaches. He made the varsity team in his sophomore year of

1912. One of his teammates was another future Army general, Omar Bradley, who

was a backup center.

Jim Thorpe grew up on the plains of Oklahoma and was sent to the Carlisle Indian

school in Pennsylvania in 1904 at the age of 16. He was a natural athlete and

excelled in track and football. The Carlisle Indian School was a place where

Indian children from the reservations were taught to read and write. It was not

technically a college, but the older students loved to play football and they

were quite good at it. In fact, the football team generated a sizeable income

for of the school, which paid for needed supplies and upgrades to the

facilities. The team traveled all over the country playing many of the top

college football teams at the time and winning a majority of their games. During

the 1912 season, Carlisle even played a game in Canada against the University of

Toronto. The first half of the game was played by American rules and the second

half was played by Canadian Rugby rules. Carlisle won the game 49-1 and the

school received $3,000.

In the summer of 1912, Thorpe traveled to Sweden and took part in the Olympics,

winning the 10-event Decathlon and the five-event Pentathlon. The Pentathlon was

a new event that was making its debut in the Olympics for the first time that

year. [The book goes into a great amount of detail about Thorpe´s trip to Sweden

and his participation in the Olympics.] His football coach at Carlisle, the

legendary Pop Warner, was also his track coach and made the trip to Sweden as

well.

Thorpe returned to Carlisle after the Olympics

for one final season in hopes of winning a national championship in football.

Carlisle was undefeated when they traveled to West Point on November 9, 1912. By

now, Thorpe was a national celebrity and every team that faced Carlisle had one

goal in mind, to stop Jim Thorpe. That was easier said than done.

Eisenhower was making quite a name for himself for his intense play on the

football field. He played running back as well as linebacker. Eisenhower had

been looking forward to facing Thorpe all season and now he finally had a

chance. He wanted to make a name for himself as the man who put Thorpe out of

the game. He and team mate Leland Hobbs decided that if they got the chance,

they would hit Thorpe with the high-low, which meant that they would tackle him

at the same time, one high, at the chest, and the other low, around the legs.

They got their chance in the fourth quarter. The hit was so violent that all

three men wound up laying on the ground for some time, recovering from the

collision. Eventually, all three got up and returned to their respective

huddles.

A few plays later, Hobbs and Eisenhower got another chance to make the same

play. Thorpe saw that he was about to be hit and stopped dead in his tracks,

causing the two Army defenders to collide into each other. Eisenhower limped off

the field with an injured knee and did not return to the game, which Carlisle

went on to win 27-6.

Eisenhower played for Army the following week in a game against Tufts, but

re-injured his knee and had to be carried off the field. Soon after, he injured

the knee a third time while trying to dismount from a horse and never played

football again. The thought of never playing football again devastated

Eisenhower. Playing football was all he wanted to do, but with that now taken

away from him, he set his sights on being the best soldier he could be.

Who knows what might have become of Dwight D. Eisenhower if he had not injured

himself while trying to tackle the great Jim Thorpe. He might never have become

the supreme commander of the Allied Forces in WWII. He might not have been the

one who gave the order to launch Operation Overlord, the D-Day invasion on June

6, 1944 and he may never have become the 34th President of the United States.

As for Thorpe, he would go on to play professional baseball for the New York

Giants as well as professional football for the Canton Bulldogs. In 1920, he was

elected the president of the American Professional Football Association, which

in 1922 changed its name to the National Football League.

When Jim Thorpe died in 1953, his family received a telegram from the President

of the United States expressing his condolences. That president was Dwight D.

Eisenhower.

Back

to Articles Menu

|