|

| |

Back

to Articles Menu

Book Report: How You Played the Game

by

Randy Snow

Originally

posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Monday, March 28, 2011

In the 1999 book, How You Played the Game,

author William A. Harper explores the life and times of Grantland Rice, one of

the first true sports writers of the early part of the 20th century. Rice is

known as the Dean of American Sports Writers and carved a niche for himself in

the field of sports reporting, something that no one had really done before. He

lived and wrote during a time known as the Golden Age of Sports, mainly the

1920īs. It was a time that included the liked of Babe Ruth, Knute Rockne, Jack

Dempsey, Ty Cobb, Red Grange and Jim Thorpe, just to name a few.

Henry

Grantland Rice, who was known as Granny to his friends, grew up in Nashville,

Tennessee. After high school, he attended the Wallace University School in 1896,

which was a college prep school. A year later he entered Vanderbilt University

where he majored in Greek and Latin, but he also studied poetry. While in

college he played baseball, football, basketball and was on the track team. Rice

was a good athlete, but not a great one. Even so, he was named captain of the

baseball team his senior year and played short stop. Henry

Grantland Rice, who was known as Granny to his friends, grew up in Nashville,

Tennessee. After high school, he attended the Wallace University School in 1896,

which was a college prep school. A year later he entered Vanderbilt University

where he majored in Greek and Latin, but he also studied poetry. While in

college he played baseball, football, basketball and was on the track team. Rice

was a good athlete, but not a great one. Even so, he was named captain of the

baseball team his senior year and played short stop.

After graduating from Vanderbilt in 1901, Rice signed with a semi-pro baseball

team and spent the summer barnstorming across the south. His family was not too

happy about his baseball playing career and they insisted that he come home and

get a "real" job. He became a reporter with the Nashville Dailey News, a brand

new newspaper that had just started up in the city. He was a sports and general

reporter with a $5.00 a week salary. Rice loved covering sports but not other

news. When it came to covering politics, he convinced a reporter from a rival

newspaper in town, the Nashville Banner, to write political articles for him. In

turn, Rice wrote sports articles for the Banner reporter, who didn't like to

cover sports.

In 1902, Rice took a new job in Georgia with the Atlanta Journal newspaper. He

again covered sports and was also assigned as the theater critic. Rice had no

interest in covering the theater so he encouraged a friend of his, Don Marquis,

to go along and write the theater reviews for him. Marquis went on to become a

famous playwright thanks to the start he got by going to the theater with

Grantland Rice.

In

Atlanta, as in Nashville, the main sport that Rice covered was baseball. He was

becoming quite well know and began receiving telegrams from several people he

did not even know telling him about an up and coming minor league baseball

player by the name of Ty Cobb. Rice began writing about Cobb and his coverage

eventually led to Cobb being signed by the Detroit Tigers. Many years later,

Cobb confessed to Rice that he himself had sent Rice the telegrams using several

false names in order to increase his exposure in the newspapers.

Rice covered all kinds of sports in Atlanta from bicycle racing, which was very

popular at the time, to baseball and college football. He covered the Georgia

Tech football team, which, at the time, was coached by John Heisman.

In 1905, he convinced his boss at the Atlanta Journal to send him to cover the

first sanctioned World Series between the Philadelphia Athletics of the American

League and New York Giants of the National League. Until then, his coverage had

only been local or regional in scope. This would be his first national sporting

event.

When he retuned to Atlanta after the World Series, he received a job offer from

the Cleveland News, another brand new newspaper. They offered Rice $50.00 per

week to be their sports editor and he accepted. Rice was so respected as a

sports reporter in Atlanta that the rival newspaper, the Atlanta News, published

a 250 word editorial in tribute to him before he left for Cleveland.

In the spring of 1906, Rice traveled with the Cleveland baseball team to Atlanta

for spring training. While there, he married his girlfriend, Katherine Hollis,

on April 11.

Grantland Rice often used poetry as part of his articles. It came very easy to

him and helped him express the events he was reporting on. When the Cleveland

baseball team finished the season with a dismal record in 1906, Rice was

inspired to write a sequel to the famous 1888 Ernest Thayer poem, "Casey at the

Bat." Rice penned the poem, "Casey's Revenge" which became almost as popular as

the original.

After a year in Cleveland, Grantland and Kate were homesick for the South. As

fate would have it, yet another new newspaper was starting up in Nashville and

Rice was offered $70.00 per week to be the sports editor of the new Nashville

Tennessean. He took the job and the Rice family, which now included a daughter,

Florence, moved to Tennessee. His sports column at the Tennessean was called

Sportsograms.

Being the only person in the Sports department, Rice worked 12-18 hour days,

seven days a week putting the sports section together. However, he still found

time to coach the Vanderbilt baseball team during the 1908 season.

In the fall of 1908, Rice not only traveled to Ann Arbor to cover the Vanderbilt

football game against Michigan, but he was also the head linesman on the

officiating crew. This was not all that unusual in the early 1900īs and Rice was

widely considered to be a very fair referee.

When the Vanderbilt Alumni Association asked Grantland Rice to write a poem to

inspire present and future alumni, he penned his poetic masterpiece called,

"Alumnus Football." While you may not recognize the title, you will surely

recognize the final lines of the poem, which have been paraphrased in sports

reporting ever since;

"For when the One Great Scorer comes to mark against your name,

He writes-not that you won or lost-but how you played the game."

After four years at the Nashville Tennessean, Rice was offered a job at the New

York Evening Mail in December 1910. The pay was not quite as good, only $50.00

per week, but he would be strictly a sports writer and columnist and would not

be involved with actually putting the paper together, so he would have more

quality time with his family. Rice took the job.

The Evening Mail was one of seven newspapers in New York that each put out two

editions everyday. It was not one of the top newspapers, but it was, after all,

in New York City.

One of the first people that Rice met upon arriving at the Evening Mail was a

fellow sportswriter and cartoonist named Rube Goldberg. Goldberg would become

famous over the years for his humorous drawings depicting elaborate and complex

ways to accomplish simple tasks.

Rice's column at the Evening Mail had several different names the first few

years. He finally settled on calling it The Sportlight. In his first official

Sportlight column on October 31, 1911, Rice reprinted his "Alumnus Football"

poem, exposing it to a whole new audience outside of Tennessee. In 1912, he also

began writing freelance articles for Collier's magazine.

By 1915, he was so well known in New York that he was offered a job at a rival

newspaper, the New York Tribune, for $280 per week. Rice accepted the offer and

took his Sportlight column with him.

Rice's Sportlight column at the New York Tribune was syndicated around the

country, which brought him national attention.

Outside of the sports world that Rice was so engrossed in, the war to end all

wars (a.k.a. World War I) was raging in Europe. Many athletes were being drafted

into military service or joining outright to do their part. Rice knew that there

were bigger things in life than covering sports so in December 1917, at the age

of 37, he too enlisted in the Army. He started out his military life at the

bottom, as a private, just like everyone else. It wasn't long before he earned a

commission as a second lieutenant and was assigned to an artillery unit.

In April 1918, he shipped out with his unit to France. In June, his unit was

ordered to the front lines, but soon after they arrived, Rice received a

reassignment to Paris to work on the Stars and Stripes, a daily newspaper for

the troops that had just started publishing in February. He was not happy about

the reassignment.

Eventually, Rice got himself reassigned

back to his artillery unit. The war ended in November 1918 and Rice returned to

the States in February 1919. Before he headed off to war, Rice had set aside

$75,000, a pretty tidy nest egg in those days, and entrusted it to a friend who

was a lawyer. The money was to be used to support his wife and daughter if he

did not return from the war. But while he was away, his friend tried investing

the money to increase it and lost it all in the process. His friend committed

suicide as Rice was returning to the States.

In the spring of 1919, Rice met Babe Ruth for the first time and the two

immediately became friends. That fall, Rice was in the press box covering the

infamous 1919 World Series between the Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati

Reds. That was the series when eight White Sox players, including Shoeless Joe

Jackson, were accused and eventually indicted in federal court of accepting

money from gamblers to lose the series.

President Warren G. Harding was an avid reader of Rice's Sportlight column.

Harding extended an invitation to Rice to play a round of golf with him and the

two hit the links in April 1921.

The 1922 World Series between the New York Yankees and the New York Giants was

the first to be broadcast live on the radio. Who better to handle the

play-by-play that Grantland Rice? It was the one and only time in his career

that Rice ever called a game. It was broadcast on radio station WJZ which had a

300 mile range.

Rice was also in the press box at the opening of the newly constructed Yankee

Stadium in 1923. It was known as "The House That Ruth Built," and Ruth did not

disappoint his fans when he hit two home runs for the Yankees during the game.

The 1923 World Series was once again played in New York between the Yankees and

the Giants and Rice was once again in the press box covering the series. But he

skipped Game 4 in order to cover a college football game at Ebbets Field between

Notre Dame and Army. However, Rice could not manage to get into the press box

and had to settle for a sideline pass for the game. On one play, all four

members of the Notre Dame backfield ran wide on an end run. They literally ran

over Rice, knocking him to the ground. He described the incident by saying,

"They're like a wild horse stampede." The following year, Rice's description of

the Notre Dame backfield would become a part of sports history forever.

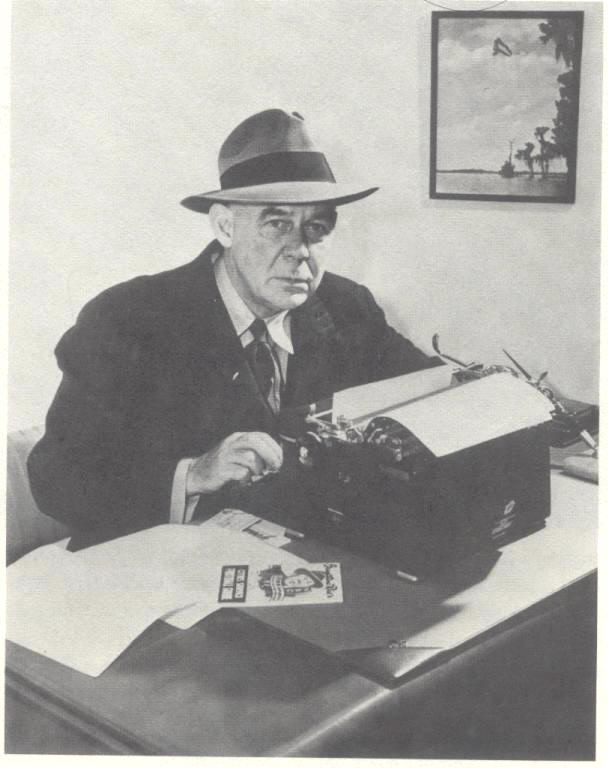

On October 18, 1924, Rice was in the press box for the Army-Notre Dame Game. He

sat at his typewriter and typed the words that would forever catapult him and

the team into legendary status;

"Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In

dramatic lore they are know as Famine, Pestilence, Destruction and Death. These

are only aliases. Their real names are Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden.

They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting

Army football team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds yesterday

afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down on the bewildering panorama spread on

the green plain below."

Rice had actually used The Four Horsemen moniker in articles before, but it

never stuck in the mind of the public until this time. He first used it in 1922

when talking about the upcoming World Series and used the phrase, The Four

Horsemen of Autumn. He used it again just weeks before the Notre Dame game when

he described the best four players on the American polo team as The Four

Horsemen of Polo.

The very same day as the Notre Dame-Army game, Harold "Red" Grange scored four

touchdowns in the opening minutes of a game between the Fighting Illini and the

visiting Michigan Wolverines. Though Rice was not there to witness the game

first hand, he began referring to Grange as a Galloping Ghost of the Gridiron.

Two games, two iconic nicknames that stand to this day, all thanks to one man,

Grantland Rice. The very same day as the Notre Dame-Army game, Harold "Red" Grange scored four

touchdowns in the opening minutes of a game between the Fighting Illini and the

visiting Michigan Wolverines. Though Rice was not there to witness the game

first hand, he began referring to Grange as a Galloping Ghost of the Gridiron.

Two games, two iconic nicknames that stand to this day, all thanks to one man,

Grantland Rice.

When Walter Camp, the Father of American Football, died in March of 1924, Rice

took over for him in selecting the annual college football All-American team.

Camp originated the tradition in 1889 and had been doing it all on his own ever

since. But when Rice took on the task, he organized a team of sports writers

from around the country to help him out. Rice continued producing the annual

list for the next 21 years, through 1946.

The newspaper that he had been writing for, the New York Tribune, merged with

the New York Herald in 1924 to become the New York Herald Tribune. In early

1930, Rice left the Herald Tribune and went to work for the North American

Newspaper Alliance. He was no longer tied to any one newspaper and was free to

cover whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted in his Sportlight column. His words

were now published in 95 newspapers around the country with a total of 10

million subscribers.

He also branched out into radio in March of 1930 and had his own half hour show

on NBC sponsored by Coca-Cola. He was also producing a series of short

Sportlight films that were shown in theaters. The film series won two Academy

Awards during its 15 years of production.

Grantland Rice covered every spot imaginable in his day, baseball, football,

golf, horseracing, the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles and the 1936 Olympics in

Berlin.

In 1948, he was featured on a new radio show called, "This is Your Life." Hosted

by Ralph Edwards, the format of the show was to bring unsuspecting celebrity

guests on and then reuniting them with people from their past. The show featured

appearances by The Four Horsemen, Jim Thorpe and coach Amos Alonzo Stagg.

After the stock market crashed in the fall of 1929, which in turn led the

country into the Great Depression, sports writing became more serious. It was a

reflection of what was going on in the world at the time, economic hardship at

home and the rise of fascist Germany in Europe. But Rice continued on the same

as he always has, with an enthusiasm and genuine love of all sports and the

athletes who played. It was Rice who first convinced his editor to allow him to

cover golf while he was working at the New York evening News when no other

newspapers were paying any attention to it. He saw the potential in the up and

coming sport not only for spectators but as a participatory game for everyone.

In 1949, Rice wrote a letter to the head of the U.S. Olympic Committee asking if

there was anything that could be done to get Jim Thorpe's Olympic medals

returned. They had been stripped from him after the 1912 games in Stockholm,

Sweden after it was learned that he had once been paid while playing baseball.

The response from the USOC was an emphatic no.

Rice had written and published several book in his time. One a collection of his

newspaper poetry and another was on golf. He also collaborated with Georgia Tech

head coach John Heisman and published a 63-page booklet called "Understanding

Football." It sold for 50 cents.

Grantland Rice died on July 13, 1954 at the age of 74. One of his last articles

that ever appeared in print was in the first issue of a new magazine that

debuted in August of 1954 called Sports Illustrated. It was an article on golf.

This quiet southern gentleman with a gift for painting pictures with his words

was the perfect person to cover the Golden Age of Sports. His Sportlight column

was read my millions of people across the country including the President of the

United States. During his lifetime he rubbed shoulders with some of the greatest

icons in sports history, and in the process, he became in icon in his own right,

outshining many of his contemporaries including Damon Runyon, Ring Lardner and

Heywood Broun.

Since 1954, the Grantland Rice Trophy has been awarded to the college football

national champion, as selected by the Football Writers Association of America.

LINKS

Grantland Rice Trophy. Football Writers Association of America

Back

to Articles Menu

|

Henry

Grantland Rice, who was known as Granny to his friends, grew up in Nashville,

Tennessee. After high school, he attended the Wallace University School in 1896,

which was a college prep school. A year later he entered Vanderbilt University

where he majored in Greek and Latin, but he also studied poetry. While in

college he played baseball, football, basketball and was on the track team. Rice

was a good athlete, but not a great one. Even so, he was named captain of the

baseball team his senior year and played short stop.

Henry

Grantland Rice, who was known as Granny to his friends, grew up in Nashville,

Tennessee. After high school, he attended the Wallace University School in 1896,

which was a college prep school. A year later he entered Vanderbilt University

where he majored in Greek and Latin, but he also studied poetry. While in

college he played baseball, football, basketball and was on the track team. Rice

was a good athlete, but not a great one. Even so, he was named captain of the

baseball team his senior year and played short stop.