|

|

|

Book Report: Integrating the Gridiron by Randy Snow Originally posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Sunday, December 4, 2011

In the 2010 book, Integrating

the Gridiron,

author Lane Demas explores the journey of black athletes as they sought to

establish themselves in college football. The book centers on four major events

that helped to bring about change in college football and eventually led to the

total integration of the sport. The first official college football game occurred on November 5, 1869 between Princeton and Rutgers. Just a few years later, William Henry Lewis became one of the country's first African American college football players in the country. He joined the freshman team at Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1888. He also played at Harvard while he was attending Harvard Law School. After graduating from Harvard, be became an assistant football coach at the Ivy League school and eventually went on to become the Assistant Attorney General of the United States. Segregation laws in the U.S., which started in the south following the Civil War, began expanding to other parts of the country and eventually had a significant impact on college sports. They were sometime called "Jim Crow" laws after a derogatory blackface character from the early days of the minstrel shows. In the late 1930īs, few teams included any African American players. If they did, they would only have one or two black players at the most. One exception was UCLA, which had five black players, and three of them were starters. There was tailback Kenneth Washington, end Woodrow Strode, lineman Johnny Wynne, end Ray Bartlett and halfback Jackie Robinson. That's right, THE Jackie Robinson. The man who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947 when he became a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers was also a star football player in college. While Robinson went on to establish himself in Major League Baseball, Strode and Washington went on to become the first African American players to integrate the NFL in 1946 when both signed with the Los Angeles Rams. Washington played just three years in the NFL due to injuries and became a Los Angeles police officer after he retired from football. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of fame in 1956. His jersey number (13) was retired by UCLA. Strode became an actor and appeared in many Hollywood movies in the 1960s and 70s. One of his most famous roles was in the movie Spartacus starring Kirk Douglas in the title role. Strode was featured in a famous scene where he and Douglas fought in the Roman Coliseum. As the number of African American players began to increase and they began to excel on the football field, racial tensions sometimes found its way onto the field. In 1950, Johnny Bright became the first player in college football run as well as pass for over 1,000 yards in a single season. He played at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. The following year, however, he was brutally assaulted on the field during a game. Thanks to Bright, Drake was 5-0 when they went on the road to play Oklahoma A&M on October 21, 1951. On the first play from scrimmage, Bright handed the ball off to a teammate and was standing behind the line of scrimmage watching the play develop. That's when Wilbanks Smith of A&M ran up to Bright and punched him in the face. In those days, players wore helmets, but there were no facemasks. The punch was so severe that Bright's jaw was broken. His jaw eventually had to be wired shut. He played very little the rest of the season. The entire incident was captured in a series of photographs taken by Donald Ultang and John Robinson. The pictures were published in the Des Moines Register the next day and they also received national exposure when they were later featured in Life Magazine as well as Time Magazine. The photos helped win Ultang and Robinson the 1952 Pulitzer Prize in Photographic Journalism. Even with the loss of playing time that season, Bright finished fifth in voting for the Heisman Trophy in 1951. In 1952, he was selected in the first round of the NFL Draft (fifth overall) by the Philadelphia Eagles. But after what happened to him in the Oklahoma A&M game, Bright was not sure how he would be received in the NFL, so he decided to head north and play pro football in the Canadian Football League. He enjoyed a very successful 14-year career in Canada where he set many league records. He started out playing for the Calgary Stampeders for a couple of years and then spent the rest of his playing career with the Edmonton Eskimos. He won three consecutive Grey Cup championships with the Eskimos in 1954, 1955 and 1956. He retired from the CFL following the 1964 season. When he was not playing football, he was a teacher and a principal at an Edmonton middle school. Bright was elected to the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 1970 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1984. Bright was still living in Edmonton when he died of a heart attack on December 14, 1983 at the age of 53. Bright's decision to play up in Canada was not as unusual as it may sound today. Many American players routinely went north of the boarder to the CFL in the 50s, 60.s and 70s if they could not get onto an NFL team because the pay was about the same in both leagues. His "defection" to Canada is very similar to that of another African American player who did the same thing some 20 years later. In 1978, quarterback Warren Moon led the University of Washington to a 27-20 win over Michigan in the Rose Bowl and he was named the game's MVP. However, he was not drafted by a single NFL team in the 1987 NFL Draft. The NFL was simply not ready for a black quarterback, so Moon signed with the CFL Edmonton Eskimos. Moon led the team to five consecutive Grey Cup championships from 1978-1982. Moon eventually signed with the Houston Oilers in 1984 and spent 17 years in the NFL. He is currently the only player who has been inducted into both the Canadian Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Drake University, which is today a Division III school, renamed its football stadium Johnny Bright Field in 2006. As disturbing as the 1951 Johnny Bright incident was, it did lead to a couple of positive changes in college football by the NCAA. For one thing, players were eventually required to wear facemasks and a new Personal Foul penalty was introduced into the rule book. Ironically, Oklahoma A&M, which changed its name to Oklahoma State in 1957, integrated its football team just a few years later. The school even produced a pair of great African American running backs who went on to star in the NFL; Thurman Thomas, who went on to play for the Buffalo Bills, and 1988 Heisman Trophy winner Barry Sander, who played for the Detroit Lions. In 1955, the issue of segregation in college football came into the national spotlight once again. This time it had to do with whether Georgia Tech was going to be allowed to play in the Sugar Bowl. Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin was not happy when he learned that Georgia Tech was scheduled to play the University of Pittsburgh in the 1956 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans. Governor Griffin, who was elected for his segregationist views, was upset because the Pittsburgh team had an African American player, fullback Bobby Grier. Griffin asked the State Board of Regents to enact a policy that would prohibit state colleges from scheduling any games, football or otherwise, against integrated schools. Students at Georgia Tech, as well as students across the country, held protests against Governor Griffin. The Board of Regents did debate the governor's request, but in the end voted 14-1 not to enact such a policy, thus clearing the way for Georgia Tech to play in the Sugar Bowl. Grier rushed for 51 yards in the game, but Pittsburgh squeaked out a 7-0 win. The game was also the first in the south to have integrated seating, meaning that black football fans were not restricted to only certain sections of the stadium. Another incident described in the book occurred at the University of Wyoming in 1969. There were 14 African American players on the Wyoming football team that season and they wanted to wear black armbands during an upcoming home game against Brigham Young University to protest the fact that the Mormon Church did not allow black church members into the priesthood of the church.  During

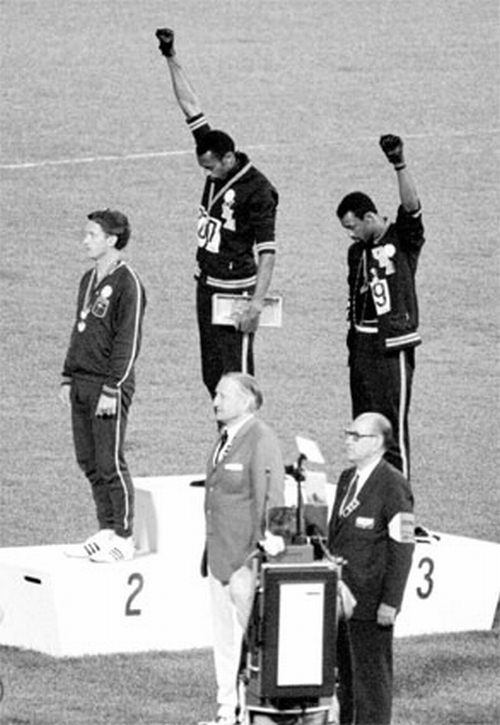

the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City, track stars Tommie Smith and John

Carlos bowed their heads and raised gloved fists in a black power salute during

their medal ceremony. Signs of protest from back student athletes were

increasing in the 1960s and when Wyoming head coach Lloyd Eaton found out about

the planned protest by his players, he dismissed all 14 from the team on October

17, 1969, the day before the BYU game. The move divided the entire state between

those who supported the players and those who supported the Coach. Ironically,

the back of the game program for the BYU game featured an ad for Chevrolet

automobiles which featured Buffalo Bills star running back O. J. Simpson.

Wyoming won the game, 40-7. During

the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City, track stars Tommie Smith and John

Carlos bowed their heads and raised gloved fists in a black power salute during

their medal ceremony. Signs of protest from back student athletes were

increasing in the 1960s and when Wyoming head coach Lloyd Eaton found out about

the planned protest by his players, he dismissed all 14 from the team on October

17, 1969, the day before the BYU game. The move divided the entire state between

those who supported the players and those who supported the Coach. Ironically,

the back of the game program for the BYU game featured an ad for Chevrolet

automobiles which featured Buffalo Bills star running back O. J. Simpson.

Wyoming won the game, 40-7.

"The Black 14," as they were dubbed in the media, took their case

to a district court in an attempt to get reinstated on the team. The players

lost the case and the subsequent appeal. Of the 14, only two returned to the

University of Wyoming and got their degrees. Another eight transferred to other

schools and also graduated with degrees. Four players even went on to play in

the NFL including Tony McGee from Battle Creek, Michigan, who enjoyed a 14-year

career playing for the Chicago Bears, New England Patriots and the Washington

Redskins.

|