|

| |

Back

to Articles Menu

Book Report:

The Big Scrum

by

Randy Snow

Originally

posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Saturday, July 9, 2011

What do

President Theodore Roosevelt and the sport of football have in common? Plenty.

In the new book, The Big Scrum, author John J. Miller tells the story of

how Roosevelt led the fight to change football from a barbaric sport into the

game we know today.

As

a Harvard freshman in 1876, Roosevelt attended the second football game ever

played between Harvard and Yale. Another freshman that year who was playing on

the Yale football team was Walter Camp, who would go on to become known as The

Father of American Football. As

a Harvard freshman in 1876, Roosevelt attended the second football game ever

played between Harvard and Yale. Another freshman that year who was playing on

the Yale football team was Walter Camp, who would go on to become known as The

Father of American Football.

Though Roosevelt never played football himself, but he was a huge fan of the

game. He graduated from Harvard in 1880 Magna Cum Lauda, ranked 21 in a class of

177 students. He then attended Columbia Law School.

In the

1800īs football was dominated by what was known as "mass momentum" plays.

Formations like the V-Trick, which was introduced by Princeton in 1884, and The

Flying Wedge, debuted by Harvard in 1892, led to many injuries on both teams.

Both formations were outlawed following the 1893 season.

On October 30, 1897, Richard von Gammon, a player on the Georgia football team,

was severely injured in a game against Virginia. He died in the hospital later

that evening from a concussion and a cracked skull. (There were no helmets worn

in those days) He was only 17 years old. The school cancelled the remainder of

the season. The Georgia Legislature even went so far as to pass a bill banning

the sport of football. The bill was vetoed, however, by Georgia Governor William

Atkinson after he received a letter from von Gammon's mother, who did not want

the sport that her son loved so much, banned.

Roosevelt remained a Harvard football fan well after his graduation, but one man

who did not like the sport was Harvard's president, Charles W. Eliot. Eliot had

tried for many years to abolish the sport at Harvard, but was out-voted every

time. Roosevelt and Eliot would have many disagreements about the sport over the

years.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Roosevelt joined the 1st U. S.

Volunteer Cavalry. The unit was nicknamed Roosevelt's Rough Riders by the media.

As a Lieutenant Colonel in the unit, Roosevelt helped to hand pick its members.

Many of the men that he chose were former football players. On July 1, 1898,

Roosevelt led the unit in the Battle of San Juan Hill in Cuba, driving Spanish

troops from the summit and forever earning himself a place in American military

history.

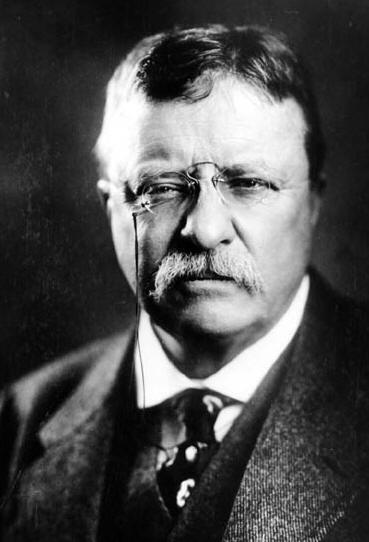

Roosevelt was elected Vice President of the United States in 1900 and, following

the assignation of President William McKinley, he was sworn in as President on

September 14, 1901. He was re-elected in 1904.

In 1905, 18 players were killed and 159 were

injured as a result of playing football. There was a strong movement by many to

ban the game altogether because of its violence and the significant threat of

serious injury.

On

October 9, 1905, Roosevelt hosted a summit at the White House with coaches from

Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Also in attendance was Walter Camp. Several

suggestions were discussed that might make the game safer for the players. Camp

was in favor of only one, which involved changing the down system from five

yards to 10 yards needed for a first down. This was something that he had been

trying to get passed for some time. He rejected many of the other ideas

including one for legalizing the forward pass. On

October 9, 1905, Roosevelt hosted a summit at the White House with coaches from

Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Also in attendance was Walter Camp. Several

suggestions were discussed that might make the game safer for the players. Camp

was in favor of only one, which involved changing the down system from five

yards to 10 yards needed for a first down. This was something that he had been

trying to get passed for some time. He rejected many of the other ideas

including one for legalizing the forward pass.

Another meeting of 13 football playing schools

was held in New York on December 8. This one was organized by Henry MacCracken,

the chancellor of New York University. Representatives from Harvard, Yale and

Princeton did not attend the meeting. The 13 schools in attendance voted 8-5 not

to ban the sport, but to change the way it was played in order to save the game.

MacCraken held another meeting on December 28, this time 68 schools sent

representatives. They voted to form their own rules committee which would

challenge the one led by Walter Camp. Eventually the two rules committees merged

and became known as the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United

States. A few years later, that organization would change its name to the

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

One of the many rules changes the new committee passed in early 1906 was the

legalization of the forward pass. This was seen as a major change to the way the

game was played. Now, instead of 22 players all bunched together in one spot on

the field trying to push or pull the ball carrier forward in a mass momentum

play, receivers were spread from sideline to sideline in what was known as an

"open style" of play.

But

even though the forward pass was now a part of the football playbook, there were

several restrictions on its use. For example, a pass could not travel more than

20 yards and, if it hit the ground without being touched by a player from either

team, it resulted in a change of possession. For those reasons, many teams did

not use the forward pass, or they did so sparingly, only when it was absolutely

necessary. Also, at the time, the ball being used was very fat and it was hard

to throw any kind of spiral. It was difficult to get the ball to go where you

wanted it to go.

For all the changes made to the rules of football, a renewed call to ban the

sport rose up again in 1909 when 26 players died from injuries sustained while

playing football. Supporters of the game persevered once again, however, and the

game continued to grow in popularity.

Even though the forward pass was there for all teams to use since 1906, many

teams, especially those on the east coast, refused to use it. Instead, they

continued to play a running style of football. It was not until 1913 when a

small, unknown catholic school from Indiana shocked the football world by

beating the mighty cadets of West Point. The passing of quarterback Gus Dorais

to wide receiver Knute Rockne made headline across the country as Notre Dame

beat Army 35-13 and brought the passing game to the forefront of college

football.

But in the end, it was Teddy Roosevelt, the man who was known to "speak softly

and carry a big stick," who set in motion the events that changed the game of

football forever. Had it not been for the 26th President of the United States,

the game of football might have disappeared all together.

Back

to Articles Menu

|

On

October 9, 1905, Roosevelt hosted a summit at the White House with coaches from

Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Also in attendance was Walter Camp. Several

suggestions were discussed that might make the game safer for the players. Camp

was in favor of only one, which involved changing the down system from five

yards to 10 yards needed for a first down. This was something that he had been

trying to get passed for some time. He rejected many of the other ideas

including one for legalizing the forward pass.

On

October 9, 1905, Roosevelt hosted a summit at the White House with coaches from

Harvard, Yale and Princeton. Also in attendance was Walter Camp. Several

suggestions were discussed that might make the game safer for the players. Camp

was in favor of only one, which involved changing the down system from five

yards to 10 yards needed for a first down. This was something that he had been

trying to get passed for some time. He rejected many of the other ideas

including one for legalizing the forward pass.