|

| |

Back

to Articles Menu

Carlisle Indian School Football Team is Subject of New Book

by

Randy Snow

Originally

posted on AmericanChronicle.com, Thursday, February 28, 2008

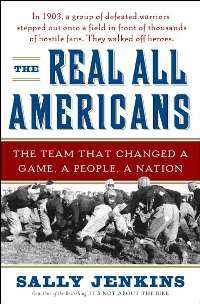

In her 2007 book, The Real All Americans,

author Sally Jenkins looks at one of the greatest football teams of the early

1900īs. The team was from a small Indian school near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

known as the Carlisle Indian School.

But the book is much more than the story of a football team. It is about a

turbulent time in American history when westward expansion of the white man

clashed with the indigenous inhabitants of the plains. The confrontations

between the two sides were often violent and bloody, but one man, who was caught

in the middle of it all, decided to do something about it.

That man was Richard Henry Pratt, a cavalry soldier who had fought during the

Civil War. After the war, Pratt spent another eight years as a Buffalo Soldier

in the Oklahoma-Texas-Kansas territories. Their job was to move tribes of

Indians into government designated reservations and out of the way of white

settlers who were expanding westward. It was during this time that Pratt, while

serving at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, witnessed first-hand the unfair treatment of

the Indian tribes by his own government. He came to sympathize and respect the

native people of the territory.

In

1875, Pratt was ordered to accompany 72 of the most violent and dangerous Indian

prisoners from the region to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. Shortly after they

arrived there, Pratt and the prisoners were relocated to Fort Marion near St.

Augustine, Florida for an indefinite period of detention. While at Fort Marion,

Pratt asked for and received permission to try and "civilize" the savage

prisoners by teaching them to read and write the white manīs language. In

1875, Pratt was ordered to accompany 72 of the most violent and dangerous Indian

prisoners from the region to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. Shortly after they

arrived there, Pratt and the prisoners were relocated to Fort Marion near St.

Augustine, Florida for an indefinite period of detention. While at Fort Marion,

Pratt asked for and received permission to try and "civilize" the savage

prisoners by teaching them to read and write the white manīs language.

Over the next three years, the prisoners worked

hard to learn everything they were taught. Eventually, in 1878, they had made so

much progress that the government released them back to their families on the

reservation. However, 22 of the prisoners/students decided to remain in the East

and continue their education. Pratt arranged for most of them to study at the

Hampton Institute in Virginia, but he knew that more needed to be done. He

wanted to help as many of the Indian children from the reservations as possible

to be accepted into American society.

Because of his success in working with the Indian prisoners at Fort Marion,

Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian School in 1879, just three years after the

battle at Little Big Horn. The school was located at the Carlisle Barracks in

central Pennsylvania, which was an old Army post that had been around since the

Revolutionary War. It had been sitting vacant ever since it was damaged during

the Civil War. Pratt liked the location of the school because most people in

Pennsylvania had never seen an Indian before. Therefore, they had no

preconceived prejudices against them the way people who lived closer to the

Indian territories had.

There was just one catch to starting up the school; the government told Pratt

that he had to include children from two very hostile Sioux tribes, the Oglala

and Brule, in the Dakota Territory, for his first class. The Department of War

and the Department of the Interior wanted to insure that these two tribes would

settle down and behave themselves while their children were "hostages" in

Prattīs care away at the school.

Surprisingly, Pratt managed to convince the leaders of the two tribes to allow

many of their children to attend Carlisle. His reasoning was that by educating

the children in the ways of the white man, they would be less susceptible to

being swindled the way the elders of the tribes had been. In October 1879, Pratt

headed back to Carlisle with 84 children from the two trides in tow, the

youngest was only10-years-old.

On November 1, 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School officially opened.

There were a total of 147 students ranging in age from six to 25 that first

year. Some of Prattīs former prisoners/students from Fort Marion, who had

remained in the East, also came to the school to help out.

Over the years, the students were taught more than just reading, writing and

math. The boys were taught useful skills like wagon building, blacksmithing,

harness making, and carpentry while the girls were taught cooking, sewing,

canning and ironing.

In the late 1800īs, the game of football was gaining in popularity all over the

country. Students at Carlisle loved the roughness of the game and organized

their own teams, playing against each other on the parade grounds. But after

several students were injured, Pratt banned the game from the school in 1890.

Students lobbied to bring the popular game back and eventually, Pratt agreed. He

realized that football would be the perfect opportunity to showcase his students

to the rest of the country. Having them compete on the football field would show

that his school was making progress in assimilating the Indians into American

culture.

In the fall of 1893, Carlisleīs first organized football team began to take

shape. The schoolīs first football coach was Vance McCormick, who had just

graduated from Yale. He was the captain of the Yale football team in 1892 and

led the Ivy League team to an undefeated 12-0 season.

The Carlisle team began intercollegiate play in 1894. Their first season

schedule consisted mainly of second tier schools which, at the time, included

Navy, Lehigh and Bucknell. They had no home field to play on, so all of

Carlisleīs games were played on the road. The team did not win many games in its

first two years, but they earned a lot of respect for the way they played the

game from the media and by the fans of the opposing teams. Unfortunately,

referees were not always kind to the Carlisle team. They often called penalties

that were not there if Carlisle showed signs of winning. At times, the calls

were so blatantly questionable that fans of the opposing teams would begin

cheering for Carlisle to show their displeasure with the biased referees.

Some of the early players on the Carlisle football team had names like Delos

Lone Wolf and Ben American Horse, which shows that even though they were living

and learning in the East, their heritage was still deeply rooted in the West.

Carlisle had its first winning season in 1896 when they posted a 6-4 record.

In 1899, Pratt hired Glenn "Pop" Warner to be the head football coach and

athletic director at Carlisle. Warner had spent the previous two years as the

head coach at Cornell University. Legendary Yale coach Walter Camp recommended

Warner to Pratt for the job.

Although Carlisle was not actually a college,

its football team played against many of the top college teams in the nation

including Michigan, Wisconsin, California, Harvard, Yale and Princeton. The

Carlisle players were much smaller than many of their opponents, but they made

up for it on the field with speed, deception and trick plays. In Warnerīs first

season with the team, they posted an 8-2 regular season record and were ranked

fourth in the nation. Their running back, Isaac Seneca, was honored by being

named a first team All-American.

In a 1903 game against Harvard, Carlisle unveiled the most controversial plays

in all of football. Warner called it the Hunchback play, but it is more commonly

known as the Hidden Ball play. As Harvard kicked off to Carlisle to start the

second half of their game, several Carlisle players gathered around the player

who had caught the ball. He then placed the ball under the back of the jersey of

one of the other players in a specially sewn compartment with elastic bands to

keep the ball in place. As the Harvard kickoff team came towards them, the

Carlisle players scattered in different directions. The lineman who had the ball

under his jersey, Charlie Dillon, raced to the end zone for a touchdown

untouched. The Harvard coaching staff protested the play, but there was no rule

against such a deception at the time, so the play stood.

Warner took a lot of criticism for the play from the media and from other

coaches. The play was never used again. Eventually, rules were put in place to

ensure that it could not be used ever again.

Towards the end of the 1903 season, the relationship between Warner and his

quarterback, James Johnson, became strained. When Warner approached Pratt about

disciplining the insubordinate student, Pratt sided with Johnson. Warner

resigned from Carlisle after the 1903 season. He returned to Cornell and became

head football coach once again. In February 1904, a 16-year-old boy by the name

of Jim Thorpe arrived at Carlisle.

In June of 1904, Pratt was relieved of his post as the superintendent of

Carlisle by the War Department after 25 years at the school. Pratt had made many

enemies in Washington over the years for siding with the Indians and against his

own government. After his "retirement," Pratt went on to lecture and write about

Indian issues.

One of the last things that Pratt did before leaving the school was to name a

new head football coach. He selected Ed Rogers, a former student at Carlisle who

had gone on to graduate from the University on Minnesota. He was the captain of

the 1903 Minnesota football team and had earned a law degree there as well.

Rogers led the 1904 Carlisle team to a 9-2 record but he was replaced after just

one season buy the new school superintendant. In 1906, the school tried to hire

University of Michigan coach Fielding Yost, but he declined.

With Pratt gone, "Pop" Warner returned to Carlisle as football coach in 1907. He

had a genuine affection for the school and the hard working players who loved

the game. Besides being a coach, Warner was a great innovator of the game and

was always looking to give his team an advantage. Like the time he had football

shaped designs sewn onto the front of the Carlisle jerseys. The idea was to

confuse the opposing team so that they would not know which player was holding

the real ball and which players were only pretending to have the ball in their

arms! He also invented shoulder pads, the reverse and various practice aids like

the tackling dummy. He even wrote the school song and varous school cheers.

Jim Thorpe grew into a fine football player for the Carlisle team. He also

participated in baseball, basketball, lacrosse and track. After winning the

Pentathlon and the Decathlon in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, Thorpe

returned to play one final season of football at Carlisle. The big game that

year was between Carlisle and Army. Thorpe was the star of the game, but the

Army team featured a future president of the United States at linebacker, Dwight

D. Eisenhower. Carlisle won the game 27-6.

The 1912 season was Thorpeīs last at Carlisle. Soon after the season ended, the

story broke that he had played baseball for money during the summers of 1909 and

1910 and he was stripped of his Olympic medals.

"Pop" Warner remained at Carlisle through the 1914 season and then became the

head football coach at Pittsburgh. He went on to coach at Stanford and Temple

before retiring from coaching in 1938 with a lifetime record of 341-118-33.

Things were never the same after Warner left Carlisle and the school played its

last season on the gridiron in 1917.

As for Carlisle itself, the school was closed in August 1918 and converted into

a hospital that treated wounded soldiers returning from World War I. During the

24 years that Carlisle competed on the gridiron (1894-1917), the football team

actually helped support the school. Profits from ticket sales helped to renovate

buildings, purchase much needed supplies and made life better for all of the

students at the school.

Today, what is left of the Carlisle Indian School is part of the U.S. Army War

College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

As for the schoolīs best know athlete, Thorpe went on play professional baseball

and football and was even the very first president of the newly formed American

Professional Football Association in 1920. The APFA changed its name to the

National Football League in 1922.

Thorpe died in 1953. The following year, the Pennsylvania towns of Mauch Chunk

and East Mauch Chunk combined to become the town of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.

Thorpe was buried there in 1954. The town is just 90 miles from the old Carlisle

School.

In 1963, Thorpe was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

A statue of him greets every visitor who enters the building. In 1982, the

International Olympic Committee reinstated Thorpeīs records and in 1983,

replicas of his 1912 Olympic gold medals were presented to two of his seven

children.

I read The Real All Americans with the sole purpose of learning more

about the fabled Carlisle football team. What I did not expect was to be pulled

into the compelling story of the plight of Native Americans at the turn of the

last century. Sally Jenkins does an excellent job of weaving both stories into

one great book. I highly recommend it.

Back

to Articles Menu

|